Flow Measurement in History

Our interest in the measurement of air and water flow is timeless. Knowledge of the direction and velocity of air flow was essential

information for all ancient navigators, and the ability to measure water flow was necessary for the fair distribution of water through

the aqueducts of such early communities as the Sumerian cities of Ur, Kish, and Mari near the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers around 5,000 B.C.

Flow Measurement Orientation

The basis of good flow meter selection is a clear understanding of the requirements of the particular application. Therefore, time should

be invested in fully evaluating the nature of the process fluid and of the overall installation.

First Steps to Choose the Right Flow Meter

The first step in flow sensor selection is to determine if the flowrate information should be continuous or totalized, and whether this information

is needed locally or remotely. If remotely, should the transmission be analog, digital, or shared? And, if shared, what is the required (minimum)

data-update frequency? Once these questions are answered, an evaluation of the properties and flow characteristics of the process fluid, and of the

piping that will accommodate the flowmeter, should take place. In order to approach this task in a systematic manner, forms have been developed,

requiring that the following types of data be filled in for each application: Download the Flowmeter Evaluation Form.

Fluid and flow characteristics

The fluid and its given and its pressure, temperature, allowable pressure drop, density (or specific gravity), conductivity, viscosity (Newtonian or not?)

and vapor pressure at maximum operating temperature are listed, together with an indication of how these properties might vary or interact. In addition,

all safety or toxicity information should be provided, together with detailed data on the fluid's composition, presence of bubbles, solids

(abrasive or soft, size of particles, fibers), tendency to coat, and light transmission qualities (opaque, translucent or transparent?).

Pressure & Temperature Ranges

Expected minimum and maximum pressure and temperature values should be given in addition to the normal operating values when selecting flowmeters.

Whether flow can reverse, whether it does not always fill the pipe, whether slug flow can develop (air-solids-liquid), whether aeration or pulsation

is likely, whether sudden temperature changes can occur, or whether special precautions are needed during cleaning and maintenance, these facts, too,

should be stated.

Piping and Installation Area

Concerning the piping and the area where the flowmeters are to be located, consider: For the piping, its direction (avoid downward flow in liquid

applications), size, material, schedule, flange-pressure rating, accessibility, up or downstream turns, valves, regulators, and available

straight-pipe run lengths. The specifying engineer must know if vibration or magnetic fields are present or possible in the area, if electric or

pneumatic power is available, if the area is classified for explosion hazards, or if there are other special requirements such as compliance

with sanitary or clean-in-place (CIP) regulations.

Key Questions to Ask when choosing a Flow Meter

1. What is the fluid being measured?

2. Do you require rate measurement and/or totalization?

3. If the liquid is not water, what viscosity is the liquid?

4. Do you require a local display on the flow meter or do you need an electronic signal output?

5. What is the minimum and maximum flowrate?

6. What is the minimum and maximum process pressure?

7. What is the minimum and maximum process temperature?

8. Is the fluid chemically compatible with the flowmeter wetted parts?

9. If this is a process application, what is the size of the pipe??

Flow rates and Accuracy

The next step is to determine the required meter range by identifying minimum and maximum flows (mass or volumetric) that will be measured.

After that, the required flow measurement accuracy is determined. Typically accuracy is specified in percentage of actual reading (AR),

in percentage of calibrated span (CS), or in percentage of full scale (FS) units. The accuracy requirements should be separately stated at

minimum, normal, and maximum flowrates. Unless you know these requirements, your flowmeter's performance may not be acceptable over its full range.

In applications where products are sold or purchased on the basis of a meter reading, absolute accuracy is critical. In other applications,

repeatability may be more important than absolute accuracy. Therefore, it is advisable to establish separately the accuracy and repeatability

requirements of each application and to state both in the specifications.

When a flowmeter's accuracy is stated in % CS or % FS units, its absolute error will rise as the measured flow rate drops. If meter error is

stated in % AR, the error in absolute terms stays the same at high or low flows. Because full scale (FS) is always a larger quantity than the

calibrated span (CS), a sensor with a % FS performance will always have a larger error than one with the same % CS specification. Therefore,

in order to compare all bids fairly, it is advisable to convert all quoted error statements into the same % AR units.

In well-prepared flow meter specifications, all accuracy statements are converted into uniform % AR units and these % AR requirements are

specified separately for minimum, normal, and maximum flows. All flowmeters specifications and bids should clearly state both the accuracy

and the repeatability of the meter at minimum, normal, and maximum flows.

Accuracy vs. Repeatability

If acceptable metering performance can be obtained from two different flow meter categories and one has no moving parts, select the

one without moving parts. Moving parts are a potential source of problems, not only for the obvious reasons of wear, lubrication, and

sensitivity to coating, but also because moving parts require clearance spaces that sometimes introduce "slippage" into the flow being

measured. Even with well maintained and calibrated meters, this unmeasured flow varies with changes in fluid viscosity and temperature.

Changes in temperature also change the internal dimensions of the meter and require compensation.

Furthermore, if one can obtain the same performance from both a full flowmeter and a point sensor, it is generally advisable to use

the flowmeter. Because point sensors do not look at the full flow, they read accurately only if they are inserted to a depth where

the flow velocity is the average of the velocity profile across the pipe. Even if this point is carefully determined at the time of

calibration, it is not likely to remain unaltered, since velocity profiles change with flowrate, viscosity, temperature, and other factors.

Mass or Volumetric Units

Before specifying a flow meter, it is also advisable to determine whether the flow information will be more useful if presented in mass

or volumetric units. When measuring the flow of compressible materials, volumetric flow is not very meaningful unless density (and sometimes

also viscosity) is constant. When the velocity (volumetric flow) of incompressible liquids is measured, the presence of suspended bubbles will

cause error; therefore, air and gas must be removed before the fluid reaches the meter. In other velocity sensors, pipe liners can cause

problems (ultrasonic), or the meter may stop functioning if the Reynolds number is too low (in vortex shedding meters, RD > 20,000 is required).

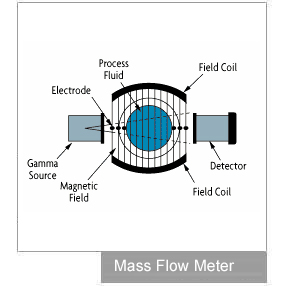

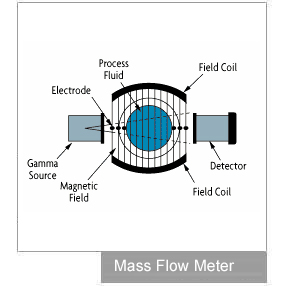

In view of these considerations, mass flowmeters, which are insensitive to density, pressure and viscosity variations and are not affected by

changes in the Reynolds number, should be kept in mind. Also underutilized in the chemical industry are the various flumes that can measure

flow in partially full pipes and can pass large floating or settleable solids.

Rotameters or Variable Area Flowmeter

Rotameters or Variable Area Flowmeter

Spring and Piston Flow Meters

Spring and Piston Flow Meters

Mass Gas Flowmeters

Mass Gas Flowmeters

Ultrasonic Flowmeters

Ultrasonic Flowmeters

Turbine Flow Meters

Turbine Flow Meters

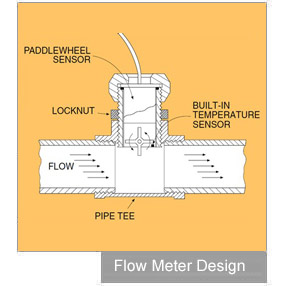

Paddlewheel Sensors

Paddlewheel Sensors

Positive Displacement Flowmeters

Positive Displacement Flowmeters

Vortex Meters

Vortex Meters

Pitot Tubes or Differential Pressure Sensor for Liquids and Gases

Pitot Tubes or Differential Pressure Sensor for Liquids and Gases

Magnetic Flow meters for Conductive Liquids

Magnetic Flow meters for Conductive Liquids

Anemometers for Air Flow Measurement

Anemometers for Air Flow Measurement